Reflecting on news from Israel and Gaza, our recent Narratives in World Politics student Anais Almi offers some thoughts about how our personal and social identities work as events unfold in the world.

Does digital media give us more or less control of our personal identity narratives?

We live in an era where our daily information is processed through digital media. We are flooded with an abundance of news and opinions daily. What do we trust? What do we believe? I will argue that digital media as an environment allows for our collective identity to rise while making our personal identity more defined and precise. I look at this through an Autonomous framework given by Weinstein, and a listener and speaker base defence from Scanlon and Shiffrin. I will also look at my personal experience through an autoethnography framework. I argue that we have seen a rise of a collective identity narrative within digital media during Covid-19. Yes, these online communities can create confusion regarding our personal identity narrative. However, through the framework chosen, I will demonstrate that this allows us as individuals to be more specific in our choices regarding 'post', 'share' or 'follow', leading us to have a more precise and defined personal identity.

Digital media as an environment embodies freedom of speech. Autonomy, as described by Weinstein, entails self-direction and living according to one's authentic desires and identity. Autonomy is compromised when others make decisions on our behalf, substituting their judgment for ours. This concept can be applied to digital media, where two defences challenge the limits on autonomy in free speech. First, Scanlon's listener-based defence argues that autonomous individuals must independently consider judgments about what to believe or do. The responsibility for any harm resulting from speech lies with individual receivers who, as autonomous agents, make choices based on the information they receive. This perspective can be linked to digital media algorithms. Second, Shiffrin's speaker-based defence posits that autonomous thinkers have an interest in knowing the contents of their own minds, thinking, exercising their imaginations, and forming authentic identities. Speech, from both speakers and listeners, is essential to realizing these interests.

This defence can also be connected to personal experiences with online communities. Our personal identity narratives are rooted in factors such as culture, language, family values, religion, and political views. Laura Roselle's study reveals a link between family history stories, memories, and political views, suggesting that family history narratives influence our political perspectives (Roselle and Husser, 2021). Examining digital media as an environment reveals its role in shaping our personal identity narratives. Digital media employ algorithms that cater content to our interests, and we actively engage with and select content that aligns with our personal identities. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the engagement in online communities surged, driven by the need for connection and shared narratives. This growth was not just about forming social groups but about creating communities that shared common narratives, as seen in movements like Black Lives Matter and Take Your Hands Off My Hijab. Individuals blended aspects of their personal identity narratives within digital media with these communities, resulting in the formation of collective identities.

Image of the model Rawdah Mohamed who started the movement on social media with this image - see https://worldhijabday.com/hands-off-my-hijab/

One can argue that being placed into such online community can confuse our personal identity. What is ours, and what is others? People's opinions come and go, but what do we make of our own? This is where the autonomous framework becomes crucia, where digital media serve as a hub for information and free speech. While external factors like location, peer influence, and political affiliations impact our online presence, we actively shape our digital identity. We make choices about what the algorithm presents to us, but it's important to note that these choices are influenced by our narrative outside the digital realm.

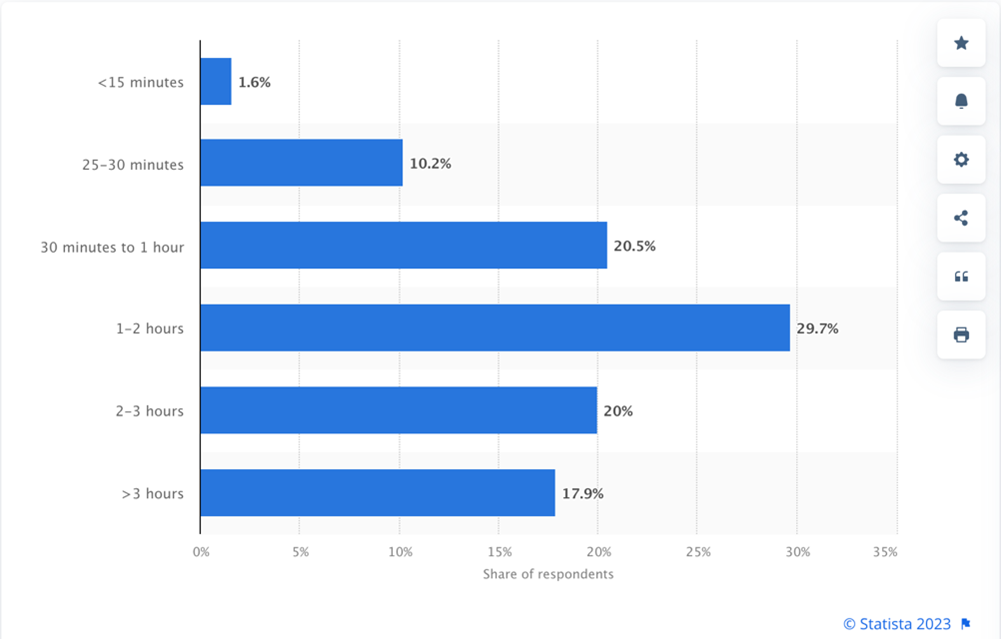

Additional daily time spent on social media platforms by users in the United States due to coronavirus pandemic as of March 2020 - see https://www.statista.com/statistics/1116148/more-time-spent-social-media-platforms-users-usa-coronavirus/

Digital media offers a multitude of perspectives on our personal identity narrative, potentially causing confusion. Two defenses emerge to address this confusion. The listener-based defense asserts that we process others' input and independently form our output. Applied to digital media, this means the algorithm may present various viewpoints on a topic, but we autonomously select the one that aligns with our personal identity narrative. The speaker-based defense argues that, to truly understand our interests, we must actively engage as both speakers and listeners. In this context, individuals influence each other's narratives, leading to the formation of collective identities in online communities. This sharing of narratives enhances our personal identity rather than overshadowing it. It encourages us to refine our personal identity by testing our beliefs against others, ensuring a more precise alignment with our true interests. Creating a collective narrative doesn't erase our personal narrative but enriches it through interaction and mutual influence.

Looking at my personal experience, I never really found myself a part of an online community. I have always identified as a Belgian and Tunisian girl who was brought up with two faiths. The way I identified had never been a problem for me; it was a conversation starter. People always seemed fascinated how two religions that hated each other could marry and let their children learn about other religions. My mom is Jewish, my dad is Muslim, and I went to a Catholic school. I have always been proud to say how I identified until May 2021, the year of me turning 20, I was faced with a dilemma my whole identity was being questioned; digital media as a whole made me question my personal identity narrative.

The Israeli and Palestinian conflict has been something I was exposed to relatively young. My parents had explained to me briefly what it was about and why people found it so great that they were married due to the stigma around the Jewish and Muslim hate. I quickly understood that this was due to historical events and lands, not the people or their beliefs. When Israel started to bomb Palestine, I genuinely couldn't understand how Israelis could be happy about it. For me, it was attacking human rights, nothing to do with religion. Israeli citizens are brought up with a different way to view this conflict that we, as Western citizens are not being taught. For them, this land is theirs. It is their due, hence why it is justifiable for them to take action for it. This is where things got confusing for me. I have many American Jewish friends online who openly took a stand for Israel; I was disgusted how they could not see they were hurting people. I also have many Muslim friends who took a stand, and most of my Western friends did too; they weren't shaming the government's action. Many were shaming the people - but not as a nationality but as a religion. It wasn't about Israel, it was about Jewish people. This is where I started to question myself, my stands, my friends, and my own narrative. Who am I? What am I supposed to support? I did not agree with the people that shamed the Jewish faith, and I did not agree with the people that were not seeing how it was purely the destruction of lives.

I was lost, but after deep reflection, I came to my senses. I did not have to fit the mould, and I took the stand, my stand which was: humanity. I posted, "I am both Muslim and Jewish - I am for human rights, not ethnic cleansing. You can be Pro-Palestine without being Anti-Semitic, so please toward your anger to the Israeli government, not the Jewish community. As Muslims, we know far too well what it is to be painted with the same brush as the evil individuals that do not represent us, so please know the difference and educate yourself before making anti-Semitic judgements." I was scared about people's reactions; I had been asked multiple times my stand and still had not answered. I became anxious, worried that I would lose friends. This post changed me, the responses I had gotten were supportive, and it turns out that many people struggled with the same dilemma as I did. By sharing my own narrative and struggle with it, people started to share their own. Together, we found a collective identity that lies in the middle of a conflict that is way bigger than us. I think if I had not taken the autonomous decision to share my thoughts, I might have never had a response to my dilemma. I might have never refined my personal identity narrative to find a collective that makes me who I am.

A Palestinian demonstrator holds a banner of the Facebook logo. © 2016 Mohammed Talatene/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

More recently in October 2023 we’ve seen a second wave of war in the Middle East. Israel was attacked and all the Western media and politicians sided with them, cutting all aid to Palestinians civilians. This time around things are different. It’s the digital narrative against the political discourse. Some people most material from inside the conflict, this video by Plestia Alaqad for instance:

When looking at social media recently I’ve been disgusted if not horrified by the things we interact with. The main thing I’ve noticed which isn’t mentioned in the mainstream media is that most religious Jews are against the Israeli government. Most of them don’t agree with the Zionist views and their take on Palestine. Palestine is undergoing a genocide in my opinion. This isn’t my personal view talking but numbers. The Western politicians all say they don’t condone act of terrorism but what about what Israel is doing?

Picture taken in a local supermarket by Yehia Hamza on Thursday the 19th of October 2023.

This second wave raised in me questions I had left behind me a while ago, things such as do I need to pick a side? Do I pick my mom’s or my dad’s side? This made me question my personal identity as well as my collective identity. But once again, I stood my ground and chose humanity. In this case I do not condone the act of terrorism by the Hamas terrorist group but neither do I agree with cutting all supplied to water, food and electricity to innocent civilians. In my opinion this war has now gone far past a conflict or an issue on religion. This has raised concerns for me about how we view communities. Why do we need to have a ‘bad guy’? Why is one right and the other wrong? I’ve noticed that many Jews and Muslims aligned against the political discourse surrounding this conflict, they all choose humanity. Of course, we always have radical people online who want their voice to be heard more than others, but how do they expect to be heard if all they do is attack someone else’s religious belief?

Online montage – no Copyright – illustrates rapid change in discourse by politicians.

I think this new era of interacting with war material first-hand really shed a light to the wider public about media biases. More and more people want justice not for them but for all both Israelis and Palestinians. Why? It is because at the end of the day they are all just humans who have a personal identity which is linked to a community identity. These identities all link due to values and morals. So why blame a religion when truly the problem is the political discourse surrounding this conflict? Many people started calling out media outlets for their bias questions and statement in favour of Israel. What doesn’t seem to make sense to me is how or more so why do they allow the Israeli government to bomb UN aid relief, schools, hospitals and much more. If we state that we do not condone terrorist acts what does this mean? Are we allowing genocide? Are we allowing civilians who have nothing to do with this die? Many pro-Israel voices say they support Palestine and are just against Hamas, but how can we explain the Israeli targets? These are all questions I cannot answer but I found refuge in my online community. None of us understand this thought process. We are all here for humanity and don’t understand why some would want to destroy others. Lastly, I’d like to go back to the algorithm. Recently it’s been promoting pro-Israeli posts and demonetizing pro-Palestine posts. Is this something we’re going to have to worry about from now on? Is our own online identity being redefined by the system?

This goes to prove that looking at digital media as an environment of autonomous freedom of speech while taking into account its defence does allow for our collective identity to rise, while making our personal identity more defined and precise. This second wave in the Middle East has raised some very interesting questions that we all can explore further.

Bibliography:

· Botticello, C. (2022). 105 Online Community Stats To Know: The Complete List (2021). [online] peerboard.com. Available at: https://peerboard.com/resources/online-community-statistics [Accessed 6 Feb. 2022].

· Dunn, T.R. and Myers, W.B. (2020). Contemporary Autoethnography Is Digital Autoethnography. Journal of Autoethnography, 1(1), pp.43–59.

· Olson, E.T. (2015). Personal Identity (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy). [online] Stanford.edu. Available at: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/identity-personal/.

· PeerBoard (2021). Users Are Tired of Social Media Groups and Are Shifting to Independent Online Communities, New Study by PeerBoard. [online] GlobeNewswire News Room. Available at: https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2021/10/26/2320953/0/en/Users-Are-Tired-of-Social-Media-Groups-and-Are-Shifting-to-Independent-Online-Communities-New-Study-by-PeerBoard.html [Accessed 6 Feb. 2022].

· Roselle, L. and Husser, Ja. (2021). The Political Consequences of Family Memories - PowerPoint Presentation. Department of Political Science and Policy Studies. PowerPoint Given in Week 3: Personal Identity Narrative for PR3498 by Laura Roselle on 31/01/2022.

· Scanlon, T. (1972). A Theory of Freedom of Expression. Philosophy & Public Affairs, [online] 1(2), pp.204–226. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2264971.

· Shiffrin, S.V. (2011). A thinker-based approach to freedom of speech. Constitutional Commentary, [online] Volume 27(Number 2). Available at: https://conservancy.umn.edu/handle/11299/163435 [Accessed 6 Feb. 2022].

· Weinstein, J. (2011). PARTICIPATORY DEMOCRACY AS THE CENTRAL VALUE OF AMERICAN FREE SPEECH DOCTRINE. Virginia Law Review, [online] 97(3), pp.491–514. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41261517?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents [Accessed 27 Feb. 2021].